Research has found that disrupted eating behaviours such as anorexia, bulimia, binge eating and orthorexia can reduce the volume of gray and white matter in a patient’s brain. This can cause issues such as increasing the likelihood of developing neurological symptoms, difficulties thinking and setting priorities, and also affecting emotional centers of the brain. As we review more research, it is increasingly apparent that hormonal restoration as well as nutritional rehabilitation are vital for recovery.

The Research

One study by Roberto and colleagues (2010) used MRI techniques to compare the brains of anorexia nervosa sufferers before and after their treatment, to women without the disorder. Their results showed that : “The correlation between BMI and volume changes suggests that starvation plays a central role in brain deficits among patients with AN, although the mechanism through which starvation impacts brain volume remains unclear.”

Another by Wagner and colleagues in 2005 looked at 40 women’s recovery from both anorexia and bulimia, over a longer term. The length of recovery ranged from 29 to 40 months, and showed that after weight restoration and nutritional rehabilitation, the brain structures of the recovered women were at the same volume as the control subjects.

The University of RWTH Aachen conducted a study in 2016 comparing the differences in grey and white matter loss between adolescents and adults suffering from AN. Researchers used meta-analysis to review 849 MRI studies. The results showed that adolescents with anorexia had a significantly greater reduction in grey matter than adults. These results have found a much higher risk of disruption in adolescents, as much of the brain’s growth occurs at this age, and disturbance has a greater negative effect. There was not enough data from adolescents to determine if long term recovery can be as complete as it is within adults, so we must remain cautious in this area.

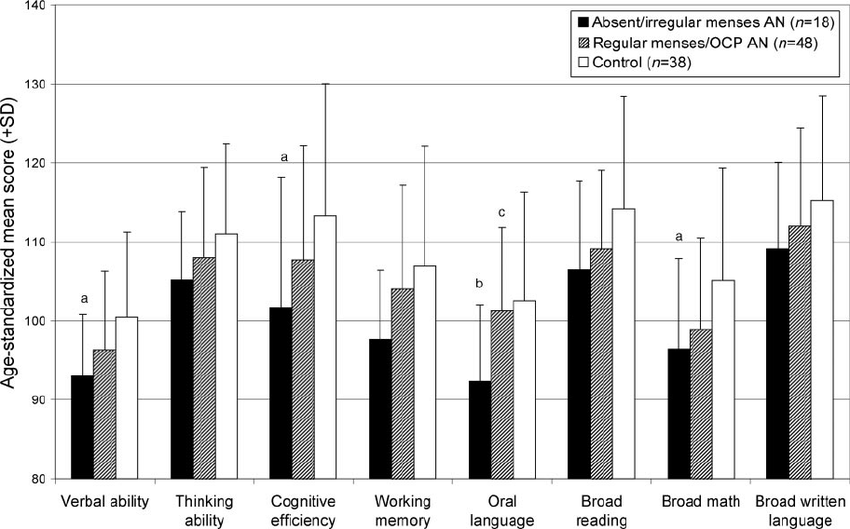

Finally, a study from Chui and colleagues (2008) used cognitive tests as well as MRI scans to gather data from 66 adult women who had experienced AN in their adolescence, compared with 42 control subjects. Again, they showed that participants that had remained underweight had abnormal MRI scans. The participants who had AN from adolescence also reported more symptoms of OCD and depression, and exhibited high cortisol levels. Crucially, when the cognitive tests were run, they showed the relationship between the absent or irregular menstrual function and cognitive function. Patients who had recovered gray matter but were absent menses were still exhibiting lower than healthy patients in verbal ability, cognitive efficiency, broad reading, broad math, and verbal recall.

Fig. 02 taken from the Chui study.

The influence of menstrual function on cognitive performance is also a feature in research on the menopause, although the mechanisms of the effect are unclear. It is possible that estrogens ability to increase blood flow in the brain makes this difference, as it has been documented that cerebral blood circulation increases in women receiving estrogen replacement therapy.

Recovering the Brain

As we can see from the research above, there is a complex relationship between hormonal health, weight and brain structure as well as function. The studies have established that long term recovery can range depending on the duration and severity of the disorder, but the type of disorder does not seem to affect the amount of damage incurred, or the recovery attainable. Following that, menstrual restoration, if maintained, seems to lead to full cognitive function after at least six months. Menses may begin to be seen as a more important marker for brain healing in the future, but there is much more we need to know. Males are woefully underrepresented in eating disorder research at present, although there is precedent to suggest testosterone restoration will have a similar effect in recovery. There is also not enough data from eating disorder sufferers in the older population, and with over 65’s in the UK unable to access some NHS clinics (as reported in the BBC recently) it is obvious that strides need to be made in these areas.

Jake Rollings

Renee Mcgregor Practice Manager

References:

Chui, H.T., Christensen, B.K., Zipursky, R.B., Richards, B.A., Hanratty, M.K., Kabani, N.J., Mikulis, D.J., Katzman, D.K., 2008. Cognitive function and brain structure in females with a history of adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa. Pediatrics 122, e426-437. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-0170

Roberto, C.A., Mayer, L.E.S., Brickman, A.M., Barnes, A., Muraskin, J., Yeung, L.-K., Steffener, J., Sy, M., Hirsch, J., Stern, Y., Walsh, B.T., 2011. Brain Tissue Volume Changes Following Weight Gain in Adults with Anorexia Nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 44. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20840

Seitz, J., Herpertz-Dahlmann, B., Konrad, K., 2016. Brain morphological changes in adolescent and adult patients with anorexia nervosa. J Neural Transm 123, 949–959. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-016-1567-9

Wagner, A., Greer, P., Bailer, U.F., Frank, G.K., Henry, S.E., Putnam, K., Meltzer, C.C., Ziolko, S.K., Hoge, J., McConaha, C., Kaye, W.H., 2006. Normal brain tissue volumes after long-term recovery in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Biol. Psychiatry 59, 291–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.014

How eating disorders affect the neurobiology of the brain, 2015. . The Emily Program. URL https://emilyprogram.com/blog/how-eating-disorders-affect-the-neurobiology-of-the-brain/ (accessed 10.25.19).